Wayne Asher tells Emma Bartholomew about the ‘lunatic’ ring road scheme that threatened to plough an eight-lane motorway through Hackney – and was only scrapped after 30 years of destroying the local property market

Pollution in London already breaches legal limits, and the A10 is a hotspot. So imagine how much worse it could be now if a motorway eight lanes wide had been built over it.

The “ringway” project was mooted in the 1944 Greater London Plan. Astonishingly, the plan hung over east London for three decades.

Its vast set of urban motorways would have transformed London beyond recognition, turning it into a city resembling LA or Houston, according to Wayne Asher.

He has written a chapter about the plans – which he believes would have gridlocked London – in the Hackney Society’s 50th anniversary book, Hackney: Portrait of a Community 1967-2017.

While two of the three proposed ringways do exist to some extent now in the form of the North Circular and the M25, a third – dubbed the Motorway Box – would have walled in inner London.

In Hackney it would have run parallel to the North London Line train tracks, from Hackney Wick to Dalston. An eight-lane flyover would have taken it over Kingsland Road – where the Kingsland shopping centre is now – towards Highbury.

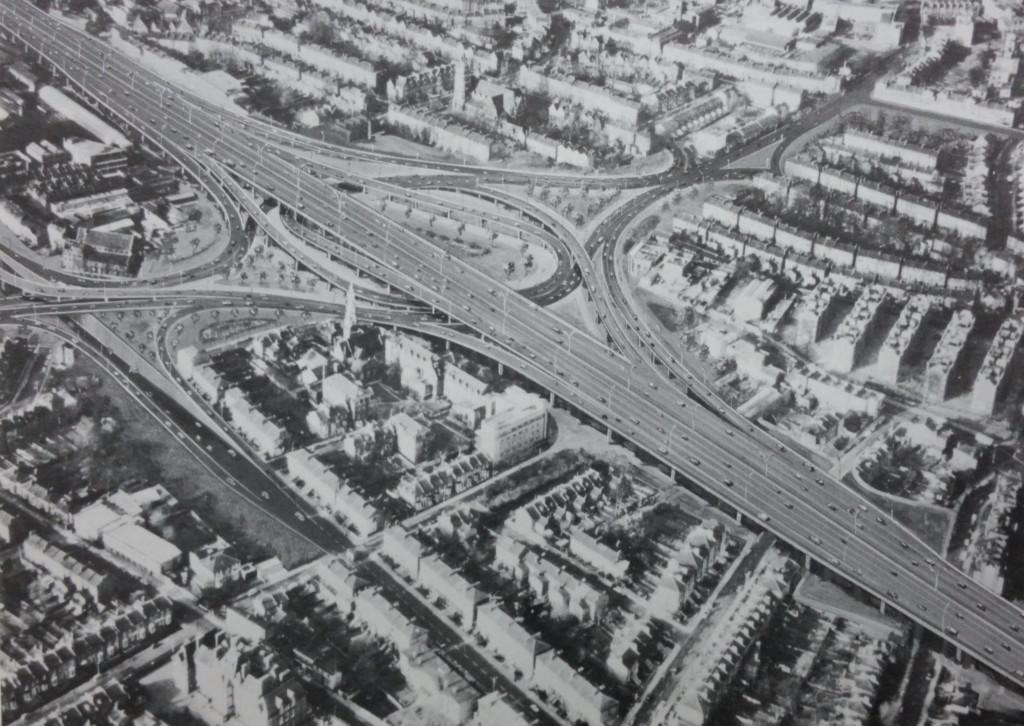

Two huge interchanges would have included a spaghetti junction at Hackney Wick where the East Cross Route now meets the A12. Another at Dalston would have been ringed by a vast gyratory system spanning Kingsland Road, Sandringham Road, Cecilia Road and Dalston Lane. The Dalston Interchange – shown in the artist’s sketch – would have been “particularly devastating” in terms of wholesale demolition, noise, pollution and a divided community.

Parts of the scheme were built, like the West Cross Route near Shepherds Bush, the North Cross Route in Brent Cross, and the East Cross Route at the Bow Interchange.

“If you have ever driven in those places you will get an idea of how horrible it would have been,” said Wayne, 59, from Stoke Newington.

”Imagine all the junctions that would be leading to get traffic onto this interchange. You can’t solve traffic problems by building roads – it would have been jam-packed with cars and it would have gridlocked the entire capital.”

He added: “Pollution would have become much worse because if you invest in road infrastructure then more people buy cars and take advantage of it.

“Public transport is so good in London but it wouldn’t have been if we built motorways criss-crossing the city. The junctions would have required so much space, it would have been impossible for pedestrians and cyclists.”

The ringways would have been Britain’s largest civil engineering project since the war. At £2billion (the equivalent of £28bn today) Wayne reckons they would have cost more than Concorde, the Channel Tunnel and a third London airport put together.

The proposed route was safeguarded by the Greater London Council, resulting in surrounding streets being “blacklisted” by building societies, meaning no one could get mortgages for houses there. Blighted properties fell into short-term use and became dilapidated or derelict. It was estimated that between 60,000 and 100,000 people would have had to be rehoused. The ringways project was finally scrapped due to public opposition in April 1973 when Labour regained control of the GLC.

Wayne, a former financial reporter on a national newspaper, has been inspired to write a whole book about the saga – Rings Around London – which will be published next year.

“There’s been no full history of what we can now call schemes, but they were taken very seriously at the time,” he said.

“If you see the images you can see the detail the engineers worked on. London had a very lucky escape from having them.

“It’s one of those bits of London history that’s worth not forgetting.” Quoting philosopher George Santayana, he added: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

“The government still wants to spend money improving roads, but we know that won’t improve congestion.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here